Congratulations to Martindale Lab Graduate Student Bailey Steinworth who was awarded Best Graduate Student Oral Presentation at the 7th annual International Cassiopea Meeting held May 10-12, 2024 in Key Largo, Florida.

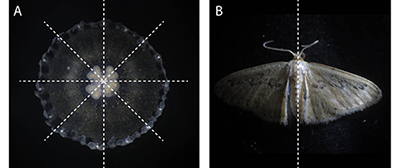

Cassiopea xamachana, the upside-down jellyfish, offers insight into how animal body plans have evolved. Biologists have traditionally thought that the ancestor of all multicellular animals was radially symmetric — that is, you would get two identical halves if you divide the animal in any plane along the central axis of its body (see A below). Other animals are bilateral, meaning they can only be divided into two identical halves through a single plane (see B below). Corals, sea anemones, and jellyfish like Cassiopea — a group collectively known as "cnidarians" — are generally considered radially symmetric and a good proxy for understanding the early evolution of animal body plans because of their phylogenetic position.

“Radial” jellyfish (A) versus “bilateral” moth (B). Dotted lines represent symmetrical axes. Photos by Brent Foster.

Bailey's talk, titled "Evidence of bilateral symmetry in Cassiopea," showed bilateral gene expression patterns in a supposedly radial jellyfish, suggesting either 1) multicellular animals actually branched from a bilaterally symmetric ancestor or 2) bilateral symmetry emerged more than once in the animal tree of life. Either interpretation challenges the classical view of how body plans evolved.

The International Cassiopea Meeting brings together researchers from around the world to share research and ideas related to the Cassiopea system. The multidisciplinary meeting gathers scientists from diverse research backgrounds, with previous attendees having a wide array of expertise in symbiosis, behavior, fluid dynamics, ecology, genetics, etc.

Meeting keynote speakers included Whitney Laboratory Associate Professor of Chemistry Dr. Sandra Loesgen whose talk title was “Cnidarian microbiomes and the chemistry of symbiosis”.