A new study just published on Nature Ecology and Evolution (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02941-y) has advanced our understanding of the principles dictating genome and gene regulation and evolution. This paper is a result of a collaboration between the Arnone, Hinman, Gómez-Skarmeta, and Maeso laboratories at the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn (IT), Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience (USA), Centro Andaluz de Biología del Desarrollo (ES), and the University of Barcelona (ES), respectively.

Echinoderms are invertebrates, and the echinoderm group includes sea urchins, sea stars, sea cucumbers, ophiuroids, and sea lilies. They are the closest phylum to chordates, a group that includes vertebrates such as humans. Importantly, just like vertebrates, they are deuterostomes, and yet they are non-vertebrates. This unique phylogenetic position allows for meaningful evolutionary comparisons between vertebrates and invertebrates. Interestingly, echinoderm larvae show bilateral symmetry, while their adult forms have pentaradial symmetry; that is, their body parts are arranged in five (or multiples of five) sections around a central axis. Animal morphology is dependent on the spatiotemporal control of gene expression, i.e., where, when, and which genes are turned on in the body and to what extent.

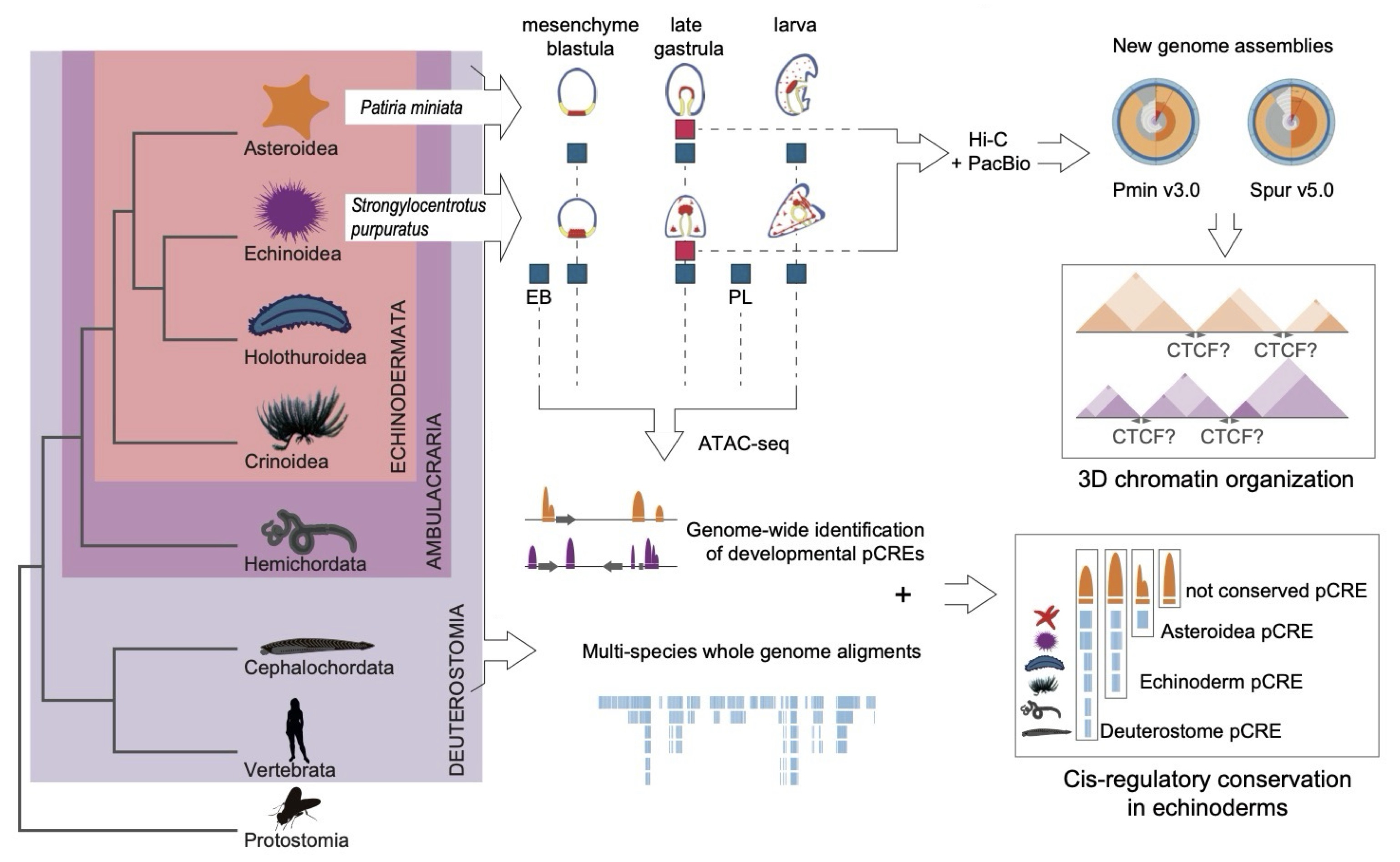

Open questions regarding the establishment of animal embryonic and adult body plans, from sponges and comb jellies to sea urchins and humans, are how each species’ genome and genes are regulated and how is chromatin folding, an essential element in gene regulation, controlled across animals? The Pacific echinoderm species, the purple sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus and the bat star Patiria miniata, have long served as key echinoderm species for evo-devo and gene regulation research. For instance recent studies have identified their adult body plans as head-like with sea urchins adopting an all-brain organization. However, previous genome assemblies for both species were highly fragmented and lacked sufficient evidence to characterize the precise genomic locations of many genes, preventing such questions from being addressed in detail.

To overcome this, we used state-of-the-art 3D genome organization identification and sequencing methods such as Hi-C and long-read sequencing. Our new assemblies approach chromosome level, and most of each assembly is contained within its largest scaffolds. This allowed us to vastly improve completeness and decrease fragmentation for both genome assemblies. Moreover, a large number of transcriptomic samples, along with the NCBI RefSeq pipeline, allowed us to annotate the new assemblies with improved precision regarding the locations and structures of genes.

Having the updated assemblies allowed us to ask questions regarding chromatin folding and the mechanisms that control genome and gene regulation. In vertebrates, a protein called CTCF is essential for organizing 3D chromatin structure by directing DNA looping and topologically associating domain (TAD) formation, whereas in non-vertebrates such as fruit flies, chromatin organization relies on other lineage-specific proteins and CTCF plays a much less prominent role. Our work showed that in echinoderms, the CTCF protein, as in other invertebrates, is not crucial for the organization of 3D chromatin structure, suggesting that the use of CTCF for long-range DNA interactions is likely a vertebrate novelty.

Among the most striking findings is the extensive conservation of regulatory DNA elements across echinoderms and other animal groups. This was revealed by comparisons of chromatin accessibility across multiple animal groups. These deeply conserved elements are most active during key stages of early development, suggesting they control fundamental developmental programs that have remained unchanged throughout animal evolution.

Overall, our findings offer a new framework for understanding how genome regulation and chromatin organization shape the evolution of animal body plans.

For more details please also read the Behind the Paper blog on Springer Nature Research Communities - https://communities.springernature.com/posts/echinoderms-as-a-paradigm-to-understand-how-genome-organization-shapes-body-plans-and-their-evolution?channel_id=behind-the-paper

Summary provided by: Maria Immacolata Arnone, Periklis Paganos, Lorenza Rusciano, Danila Voronov